Completed in 1880, the narrow-gauge NCRR ran from the silver and gold mining center Austin to Battle Mountain (a town that never saw a battle and sits in a valley), where it connected with the Central Pacific's transcontinental line. How the railroad came to be is a story in itself. After a bitter fight, the Nevada legislature (overrideing the Governor's veto) authorized $200,000 as a Lander County subsidiary bond fund for the building of a railroad to serve the mines around Austin. Of course, there was a bit of western "politics" involved: the state senator that ramrodded this through was also the Secretary of the Manhattan Silver Mining Company, who owned most of the mining claims in the area, and whose company would pretty much solely benefit from the line's existence. The stipulation was that the line had to be built within five years.

|

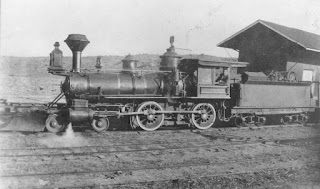

| No. 5 in about 1885. CSRM Collection |

|

| No. 5 in better days. CSRM collection |

NCRR renamed the locomtive the General J.H. Ledlie, after the Union general who had been involved with the original building of the Nevada Central. It was an ignomious name, as General Ledlie had been cashiered from the service for dereliction of duty, having been drunk in his bunker when he was supposed to be leading his troops in a charge during Battle of the Crater, part of the Siege of Petersburg. Because of the general's absence, his troops were slaughtered.

In 1881, the Union Pacific had the idea of competing with the CP and building their own line across Nevada, to take advantage of the mining traffic. They bought the Nevada Central as a piece of that puzzle, but the mining bust led them to back away from the plan, and in October 1884 they purposely defaulted on an interest payment, letting the NCRR fall into receivership. Four years later and renamed the Nevada Central Railroad, the company pressed on under local ownership by the Stokes family.

The Nevada Central continually struggled with solvency, and could only generate a decent profit if all the mines around Austin were in full production. Most mining had ended by 1911, and the company survived - barely - by relying on wool and cattle traffic. By the mid-1930s, not even that was enough, and so on December 20, 1937, the Federal Interstate Commerce Commision authorized the line's abandonment and on January 31, 1938 all operations ceased and the Nevada Central was backrupt for the last time, Most of the equipment was sold for scrap. Most, but not all. No. 5 had continued to operate pretty much to the end, but instead of being scrapped, it was acquired by NCRR's General Manager, J. M. Hiskey, who then loaned it to the Pacific Coast Chapter of the Railway & Locomotive Historical Society.

In December, 1938, the locomotive was transported to the Southern Pacific shops in Berkeley, where she was gussied up to look like Central Pacific No. 60, the Jupiter, and (along with sister No. 6), was used to stage the famous driving of the Golden Spike ceremony at 1939 Golden Gate Exposition, a show produced by Art Linkletter. Our photo, then, was probably taken some time in late 1938.

|

| On display at the CSRM. Photo linked from the CSRM page. |

One final note from the perspective of a researcher: had the owner of this photo not written "Battle Mountain Nev" on it, this would have likely remained a completely anonymous photograph, without much of a clue (other than the "5") to begin researching. So, I'm very thankful that someone took the time to note where this photo was taken!

Some of the references I've drawn on for this story:

- Survivors from the Industrial Past, a post from Roger Colton's The Blue Parrot blog

- Utah Rails' history page

- The Pacific Coast Narrow Gauge blog

- CSRM's page describing the locomotive as currently displayed

No comments:

Post a Comment